“Listen,” my dad said. “Be a good listener.”

“Listen,” my dad said. “Be a good listener.”

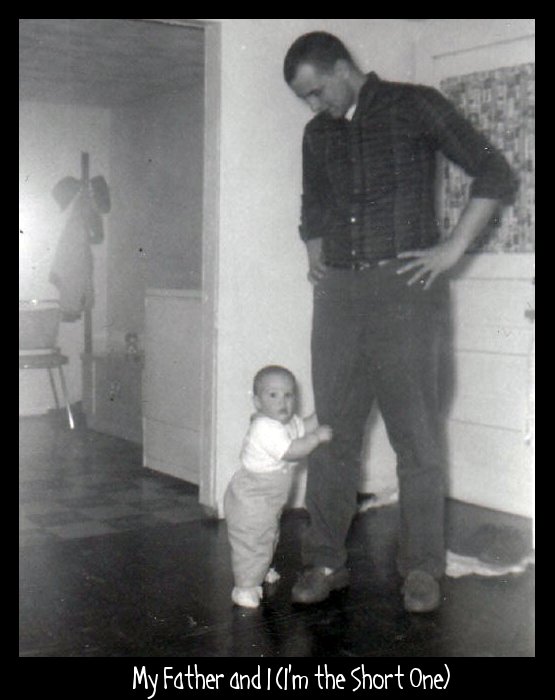

I grew up as a fan of superheroes, sure, and of mountain men, and of good-guy gunslingers who disappeared after the town was saved, and of self-less soldiers, and of super-sleuth detectives (and we can’t forget NINJAS), and of all sorts of heroic types my dad and I watched together in movies . . . and of amateur and professional athletes, of course, but for me there was really only one true hero. Only one adult of whom I was the biggest fan.

MY DAD!

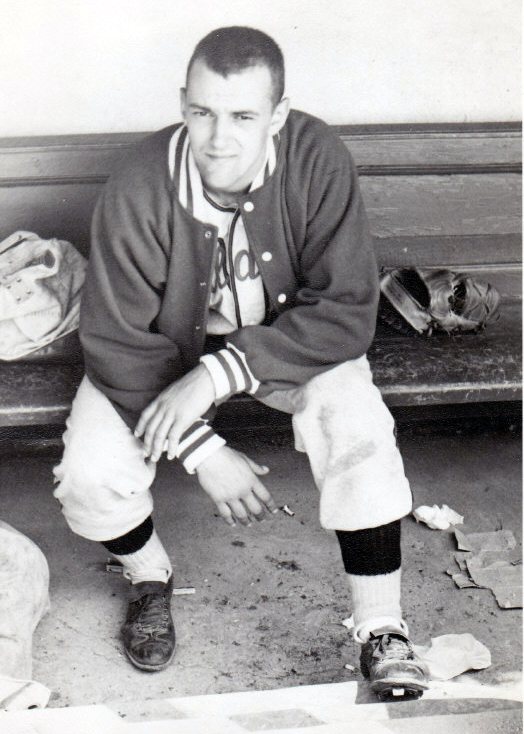

I’m not just talking that common boyhood idolization of someone who could do just about anything. It wasn’t just about his physical strength or his vigor, nor his confidence, nor his ability to figure things out, nor his super-fine motor skills which he demonstrated on the field and the court and the course.

All those things certainly influenced the level of awe and admiration I had for him (and still have).

But it was more than that, really, much more, that made me look up to my dad so much.

He never went to college. Back then, most people didn’t. He did, however, have specialized training in several areas – first while in the Army years before I was born, then after he got back home as an apprentice in a trade that required the use of mathematics and intricate measurements on a daily basis, not to mention a lot of physical labor.

My dad worked hard for most of my life. Actually, from the get go, that’s all I knew him as – this hard-working man, this talented athlete and this great coach (for me and for several teams over the years), this very loving father.

My dad has also been (and still is) one of my greatest teachers.

Not about books or academics, but about life, about living. Things that have shaped me. That have even shaped my writing (not to mention my chasing my dream in the first place).

He’s taught me many things through his words of advice and through his actions.

Sometimes by sitting me down and sharing an insight in response to an event, but mostly with a few simple words that were just part of some regular old conversation.

He taught me that compassion and empathy and tenderness are not signs of weakness, but of a different kind of strength, a more important one, built on kindness and consideration and love.

He taught me humility through his own ability to avoid bragging despite being an exceptional athlete.

And also by saying, “a guy who has to tell other people how good he is at something must not be that good, really, or they’d already know. Let your actions speak for you.”

This wasn’t just a sports-related truth, but an everyday everywhere sort of truth. One I still try to live by as best I can, by doing the best I can.

He taught me to judge a person based on my experience with that person, not based on the opinion of others. Not based on some common perception. And not based on a person’s station in life (i.e. if you come across a homeless person, he told me, treat them the way you would the CEO of a Fortune 500 Company . . . they’re just as important . . . and you might be shocked to discover how many people in such dire situations were in such powerful positions at one time). The opposite could also be said to be true: don’t assume that people of status and “importance” are any better or truly more important than anyone else.

Don’t judge a person based on his circumstances, but based on his character, he told me. Based on how he treats you. On the way you witness him treating others.

“Be a good listener,” he also said.

As a matter of fact, he told me many, many, many times, that it’s better to listen than to speak. Not being didactic, but always in the middle of some other conversation. Because listening is a value in which he truly believes, just like kindness and forgiveness and acceptance of those who are different.

I believe that my deep-rooted affinity for those who are different, for misfits in one way or another, was the product of my dad’s assertion that I could learn something from anyone. From everyone!

I think (in addition to my own experience as a misfit, as someone different) that’s not just why I embrace those who are different, but why I feel compelled to examine their lives, to write about them, to try to understand them, and to learn everything I can from them.

Although my dad used the word “listen,” he also conveyed the essential difference between listening and hearing. Between simply noticing the sound of another person’s voice and receiving/considering/understanding the meaning behind the words being shared.

That one bit of advice has certainly informed much of my life. It has allowed me to form some truly remarkable relationships with all sorts of people from all walks of life.

It has also proven to be very useful to my writing from three primary perspectives:

I. my attempts to capture authentic dialogue and characterization

II. by listening to my characters rather than forcing upon them my own preconceptions

III. by finally listening to my true self when it comes to what I want to do and to be, and in trying to find ways to honor that while still being responsible for things like bills, relationships, and so on

I’m currently working on a YA novel-in-verse, titled A Boy Called Mo, about a football player who is bullied. One poem I’ve written for that manuscript was inspired by “Those Winter Sundays” by Robert Hayden, a wonderful poem of tribute and thanks to the things a father does that don’t often get noticed by us in our youth. Or that don’t often ever receive any sort of external recogonition or expressed gratitude. The very things that define fatherhood. The very things for which we should be most thankful.

And I am. Profoundly. Thank you, Dad.

I can’t post my poem here, as I just learned it’s been accepted for publication in the awesome literary journal Hunger Mountain (due out Spring 2015), but I can share the sentiment of Hayden’s poem and of my poem here:

“I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking.

When the rooms were warm, he’d call,

and slowly I would rise and dress . . .”

(from Robert Hayden’s “Those Winter Sundays”)

Most everything we have, as children, are given to us . . . starting with our lives. We tend to take all of that for granted and seldom stop to thank those who make it possible.

In addition to the life and the love and the material things my dad had a hand in giving me, I also want to thank him for his advice and his wisdom, some of which he shared with me intentionally. Much of which he just demonstrated every day.

As teens we resist the idea that we can continue to learn (or that we might need to) from our parents. As adults, we often realize we can learn from everyone – chilren, parents, strangers, and from those parts of us we may have not even known were there, parts we may have long thought extinct, the often silent parts that aren’t really silent, they’re just so hushed we only hear them when we stop . . . when we listen. Especially if we stop and we listen.