“What we see depends mainly on what we look for.” – John Lubbock

There are two small scenes in my favorite novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, that reveal a truth I had never contemplated until I was in my twenties: how we tend to see the people in our lives who were here before us only as the person they are to us, not as someone who’s lived another life.

It’s a perspective thing.

The first scene I’m alluding to is when Scout and Jem watch their dad, Atticus (the man they perceive as so-old-he-can’t-play-football-or-do-much-of-anything-worth-doing-outside-a-courtroom), as he’s asked by Sheriff Tate to shoot a rabid dog and Atticus does this seemingly impossible feat with his one and only shot.

The surprising prowess Atticus demonstrates in that scene, of course, is juxtaposed against his inability to win the larger battle he’s currently fighting, but through the responses of Jem and Scout it also reveals how, when we’re born, we enter into all these other lives.

We just tend to get so caught up in our own that we don’t often recognize the parts of our story that came before us.

And how would we even know to look?

Jem and Scout never knew that Atticus was a marksman when he was a boy. In part, because the man they’ve known their whole lives has always been that, a man: the mature, kind, humble dad, Atticus. They never knew the boy, Atticus, the way they know Dill, or even Walter Cunningham.

One of the many wonders of writing is the opportunity it offers to slow down and to explore the life of that boy or that girl you never knew. Or to imagine that other life.

The second scene happens later in the story, when Scout and Jem go to church with Calpurnia, the woman who has helped raise them. They observe the way she acts and talks to members of her congregation and she seems so different from the Cal they know.

It’s after this scene that Scout sees Cal as more than the black woman who works for the Finch family. She sees her as having two lives, and two identities, yet also as more than either one by itself.

She sees Cal as more.

Sometimes it’s not until after they’re gone from our lives that we notice the person we didn’t really know there beneath the surface of the one we did.

It’s as if our families – our parents, grandparents, aunts and uncles – are secret agents who’ve lived these double lives. Of course, it seems that way simply because we tend to view people from the perspective of how they fit into our lives (not how we fit into theirs).

During the first half of my life, my gramps was simply my gramps (okay, sure, he was my mom’s dad, but that sort of became his secondary title with regards to me).

Whether fiction or nonfiction, stories can reveal the layers of a life.

My gramps was a quiet man. For much of my youth, he sold used cars. He could fix anything with his hands. Hands, by the way, that he’d managed to blow the fingertips off during an accident when he was a boy

I used to marvel at the way he could take just about anything apart and tinker with it and put it back together better than it had been. The way those fingerstubs never got in the way, never slowed him down.

That’s the sort of thing, I suppose, that might just get a kid to ask questions about a man’s past. Like, “How did you lose your fingers?!?”

It’s definitely the sort of thing that makes you imagine a dozen different ways it could have happened (to even write poems and novels about it). But the quietness, the ever-smiling, soft-speaking, car-selling traits, those things seemed to be my gramps (even though it was the other way around, even though he was those things . . . and so much more).

Those weren’t the sort of traits you asked questions about. Not the sort that seemed to come with any mysterious backstory. So I never asked.

Here’s something I never knew about my gramps until after he died: he was a hobo!

He had six brothers and sisters (not to mention another sibling who died as a baby) and his family, like so many families, couldn’t make ends meet. So, he quit school. He’d made it to eighth grade after all. Of course, had I known that when I’d watched him with his wizard hands, it would have made the magic all the more unbelievable. Had I known that smart, soft-spoken, simple old man never even got to high school, I may have been more surprised by the things he did.

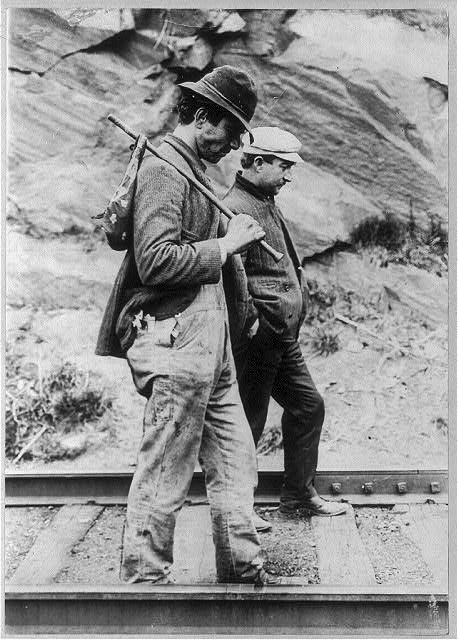

Had I known that, at fourteen, my gramps left home and became a hobo, a tramp, a bindle stiff, hopping trains and traveling all over the country to find work so he could send money home to help his mom take care of his brothers and sisters, I’d have seen in him someone I never knew. Even though that part of him was always there beneath (or behind, or at least years before) the version of him I did know.

When I first started to uncover stories about the hobo boy my gramps had been, it was like, with each new telling, with each new episode, he grew this new skin, this new face, even though the truth was he’d always been that person underneath. I’d just never seen him there.

I’d never thought to look.

Maybe that’s why one of the themes in my novels and in my poetry has to do with the way we tend to see each other. And to not see each other. How preconceptions and reality don’t always line up and how that can be a wonderful thing, really, if we do ever stop and look.

That’s part of the writer’s quest, isn’t it? To stop. To look.

Mary Oliver says: “our duty as writers begins not with our own feelings, but with the powers of observing.” Only I don’t think she means just observing what’s going on around us now, but also observing the things that happened before we ever showed up.

Mr. Bones, the character in my YA novel by the same name, has parts of my gramps in him – the vagabond parts, the tramping at fourteen parts. But there are other people in him too, including me. I think that’s one of the reasons I love discovering a bit more each time I sit at the page and spend time with Mr. Bones.

In a way, I’m learning about my own gramps. Seeing him through my new eyes. Because now I’m looking. And the things I’m finding out (the fun and the difficult) fascinate me.

Which reminds me, I’d better get to the page for a bit. It’s time to write, after all. Time to remember. Time to imagine. Time to consider the lives of all the people I grew up with – the known lives and the unknown. As well as the ones I invent.

Photo credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, [reproduction number, LC-USZ62-50739]